Clockwise has become quite a standard term in games of nearly every type, and is often nearly overlooked when learning or teaching a game’s rules. However, at its core this simple term succinctly describes one version of a foundational mechanic that influences every tabletop game to some degree.

Each tabletop game designer needs to determine how to handle players’ turns in each game, and though that part of games is frequently taken for granted, irregular turn order offers a lot of potential to adjust the mechanics of a game in fun and interesting ways!

Overview of Irregular Turn Order

As mentioned above, a key part of most games is player turn order. Irregular turn order refers to any game that varies from the default pattern of circling the table with each player taking a turn. For the purpose of turn order as a tabletop game mechanic, clockwise and counterclockwise are just about the same thing as they each go player by player with no variation.

Varying the turn order in games can do a lot to help games become more thematic, can help players be more engaged, and can help game experiences feel fresh and new each time. I have found both that considering an irregular turn order can help spark new game ideas, and that considering a variety of turn orders for a specific game idea helps that idea develop further and can really add a lot more strength to the design.

Important Considerations with Irregular Turn Order

Below, let’s briefly review a handful of possible turn order variations, as well as some of their potential implications for the games that we design and create.

Clockwise and Counterclockwise Turn Order: This is often the default option for board and card games. Each player takes a turn in order of where the players are seated, and continue doing so until the end of the game. This offers a nice, even, measured approach to the game that requires little extra thought so that players can focus on other aspects of the game.

Player-Driven Turn Order: This category of turn order variation gives players some interesting opportunities as they take a major role in selecting the turn order each round. This often invites designers to consider opportunity cost, fixed cost, or bidding mechanics that give players a trade-off of ideal turn positions for a higher cost. Player-selected turn order describes a number of possible ways of determining turn order, including the following:

- Auction Turn Order: In some games, players bid for turn order in some type of auction, which may vary in how it is conducted using different auctioning methods.

- Benefit-Based Turn Order:Each turn players have the opportunity to choose more valuable benefits paired with later turns the following round, or less valuable benefits or even penalties paired with earlier turns the following round. Kingdomino is one good example of this, as if players select better tiles, they take a later turn the next round.

- Action-Based Turn Order: In a number of games, the order in which players take a specified action (often passing) determines turn order. Pass order can either determine the first player the next round, or dictate the order of every turn that occurs after that. Azul is an example of a game that determines the first player each round by the player who takes a penalty tile first.

Process-Driven Turn Order: This category of turn order variation describes instances where players’ turn order is not quite random, nor completely consciously chosen, but rather driven by a game-managed process that players can often influence to some greater or lesser degree. Variations under this category include the following:

- Position-Based Turn Order: Players’ turn order could be determined by their position in the game. For example, a game might let the player with the least points go first and the player with the most points go last, giving behind players a chance at catching up.

- Action Cost Turn Order: Related to the above idea, a game could also have some kind of other track that determines turn order, which adds a turn priority cost to more powerful actions, and a turn priority benefit to less powerful actions, creating additional trade-offs throughout the game.

- Action-Claiming Turn Order: This is another method of giving players a limited amount of choice in turn order throughout the game. This describes games where turn order is determined by the order in which actions are taken or claimed. The game Broom Service is a good example of this, as going first is a disadvantage, so each player to last claim a main action (use a brave witch) begins the next round, which does a good job of balancing who is able to take main actions. One of our upcoming games, Golddigger’s Mine, employs this mechanic as well, in an adjusted way that permits the first players of a card to select a replacement card, and makes sure that all players receive a full turn.

Game-Driven Turn Order: This category of turn order variation describes games that have a built-in mechanic that decides the first player with no conscious input from the game players. This can still help support gameplay, balance, or theme in interesting ways, even though turn order is not a decision players need to consider.

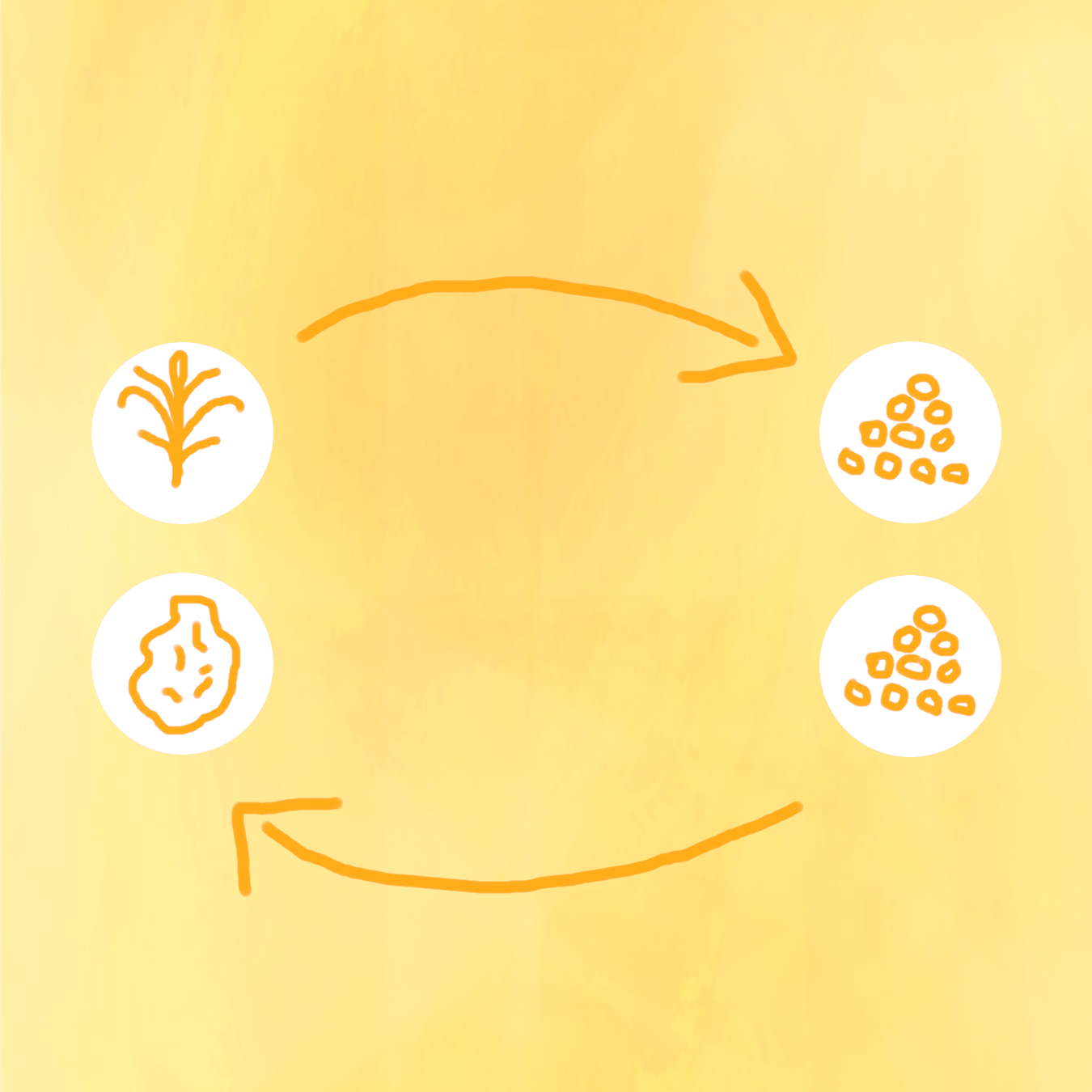

- Progressive and Regressive Turn Order: Progressive turn order describes a game played in rounds, where each round the role of first player progresses to the following player, making the previous first player now become the last player for the next round. Skull King uses this turn order variation in order to help balance the game in important ways. Regressive turn order does the same thing in an opposite way, making the last player each round the new first player, the previous first player the new second player, and so forth.

- Role-Based Turn Order: In some games where players take on various roles, a specific role may be assigned to be the first player of each game or round. Alternatively, roles can completely dictate the order of all turns, as players might secretly select a role that is then revealed or acted on when it is time for that role to take a turn. One Night Ultimate Werewolf is one example of this variation.

- Random Turn Order: Games where players’ turns are completely random are less common, but one way of doing this is to have players randomly select numbers or other things that immediately show which order players take their turns in.

Simultaneous Turn Order: This category includes games like Sushi Go, and describes games where distinct turns are still important, but each player takes a turn at the same time, waiting until all have finished before beginning the next turn together.

No Turn Order: This final variation describes games that ignore turns altogether, and often engages players in a race to complete an objectives following the game’s rules. A few examples of games with no turn order include Dutch Blitz, Big Fish, Lil’ Fish, and Wacky Six.

Cautions and Tips for Using Irregular Turn Order

Irregular turn order can add a lot of fun variety and interesting thematic decisions to games, but the decision to use irregular turn order should be carefully made with the variation carefully explained, as varying the regular pattern of turn orders can sometimes confuse players or make the learning curve a little bit steeper.

In addition to this, be sure that your variations in player turn order contribute to the theme and feel and flow of the game rather than detract from it. There are a lot of fun things designers can do with irregular turn orders, and I’d love to hear your thoughts and ideas with ways it can be used!

What are some interesting ways you have seen irregular turn order be used as a part of a game? How else can irregular turn order be used strategically? Please comment below with your thoughts!

Irregular turn order refers to any game that varies from the default pattern of circling the table with each player taking a turn.

Examples of Games that use Irregular Turn Order

- 7 Wonders

- Azul

- Big Fish, Lil’ Fish

- Broom Service

- Dutch Blitz

- Kingdomino

- One Night Ultimate Werewolf

- Pit

- Skull King

- Sushi Go!

- The Resistance

- Wacky Six

- Werewolf

Other Tabletop Game Mechanics to Explore

- Action Drafting Mechanic

- Alliances Mechanic

- Auctioning Mechanic (Part 1/2)

- Auctioning Mechanic (Part 2/2)

- Bluffing Mechanic

- Board Game Mechanics: An Overview

- Component Drafting Mechanic

- Cooperation Mechanic

- Dice Rolling Mechanic

- Direct Conflict Mechanic

- Elimination Mechanic

- Engine Building Mechanic

- Finance Mechanic

- Irregular Turn Order Mechanic

- Memory Mechanic

- Negotiation Mechanic

- Random Selection

- Social Deduction Mechanic

- Tile Placement Mechanic

- Unique Abilities Mechanic

- Worker Placement Mechanic

Are there other game mechanics or topics that you would like to see explored further? Please comment below with any requests!